January is a time for shaking off the excesses of Christmas and considering the new year ahead. For those in charge of UK defined benefit pension schemes, it is important to be aware that life expectancies are due to fall again in 2023. A combination of COVID, healthcare pressures and other factors have led to 2022 being another heavy year for UK mortality and the third in a row following the COVID pandemic. Based on provisional full-year data from the Office for National Statistics (excluding 31 December which will be available next week), there were 576,896 deaths registered in England and Wales in 2022 representing the greatest number since 1993 (ignoring 2020 and 2021). Furthermore, analysis by the Continuous Mortality Investigation (CMI) – the Actuarial Profession’s mortality arm – which takes account of how the size and age structure of the population changes over time, confirms that the age-standardised mortality in 2022 was 4.8% worse than pre-pandemic levels in 2019 and that there were around 31,000 more deaths in the UK than would have been expected based on pre-pandemic mortality (also known as “excess deaths”).

Whilst 2020 and 2021 were largely ignored as being exceptional by pension schemes and insurers when setting life expectancy assumptions, the continuation of heavy mortality into 2022 will most likely not be and could reduce views on life expectancy significantly. Life expectancy for the typical 65-year-old pension scheme member will automatically reduce to reflect the 2022 data when the CMI releases the 2022 iteration of its annual mortality projection model in June. Coupled with the impact of the population estimate restatements arising from the 2021 census, the reduction from the 2022 CMI model could be as much as 4% or 10 months, giving rise to significant funding level improvements of a similar magnitude. However, this depends on the view taken on the future path of longevity and whether 2022 is seen as indicative of the path for future UK mortality. The CMI may dampen the impact from the new data by adjusting the model and a more realistic prediction may be to expect a life expectancy reduction of around 2%.

This is clearly a bad news story from a human perspective, but it could push schemes closer to or beyond their long-term funding or longevity risk reduction goals. It may also create a positive balance sheet impact for sponsors and in some circumstances curtail deficit contributions. However, trustees and sponsors who have already made an advance allowance for the impact of COVID in their life expectancy assumptions need to be careful not to double count the effect when the latest CMI model projection model is adopted. Similarly, whilst this may make longevity risk reduction options look cheaper, it depends on the timing of and extent to which it changes insurer life expectancy pricing assumptions (which look to have already reduced in the last year). The impact on your scheme will require careful consideration and judgement, with advice from your actuary.

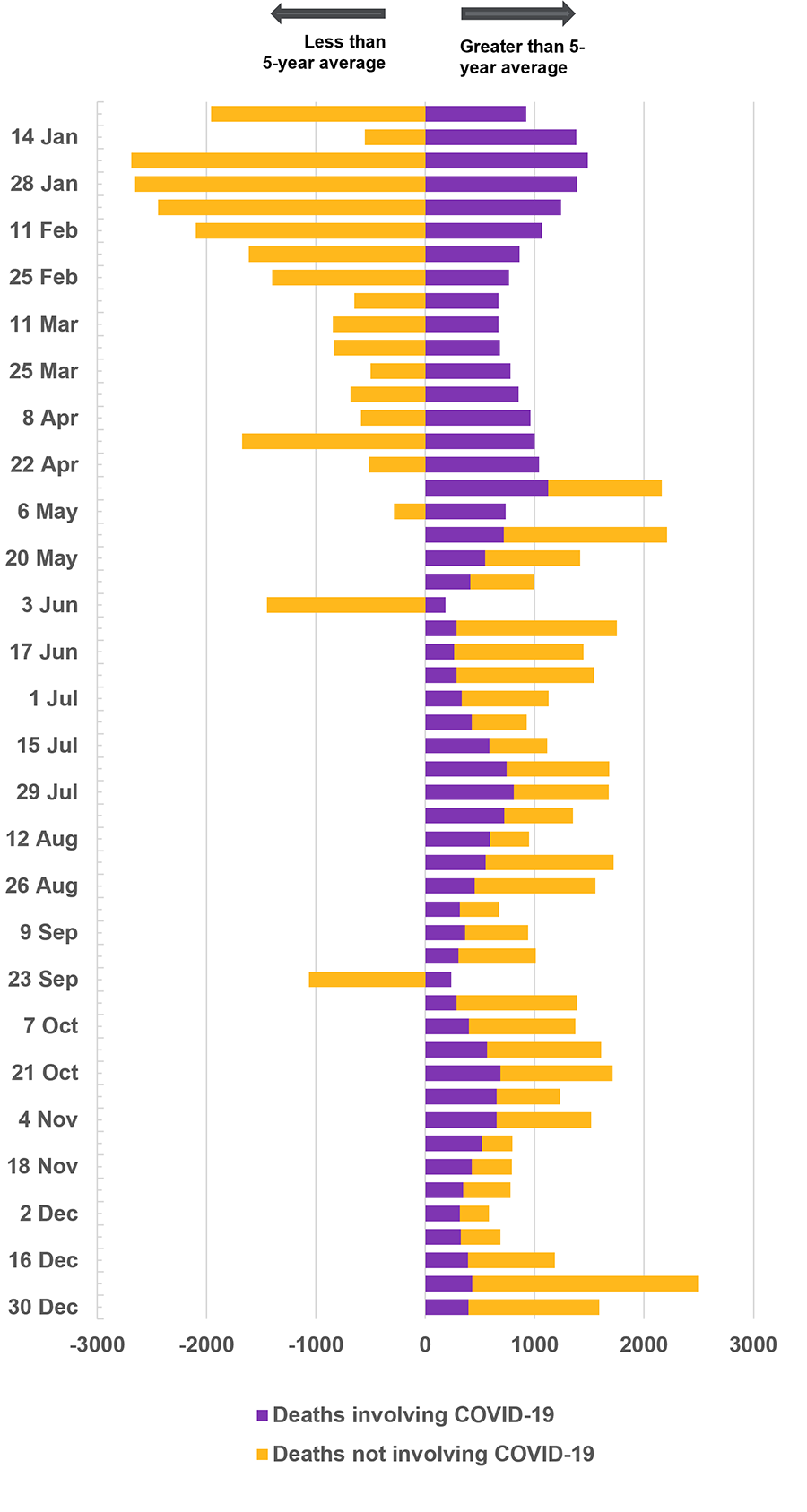

Let’s look at the data and causes more closely. Whilst mortality in the first half of the year was in line with 2019, the dip in mortality usually experienced in Summer did not fully materialise. By the end of Autumn, year-to-date mortality was running at around 4% above pre-pandemic levels in 2019 and remained so by the end of the year. (This compares with mortality increases of 13% in 2020 and 7% in 2021 relative to 2019.) According to data from the ONS, there were c12,800 deaths registered in England and Wales that involved COVID in the second half of 2022, whereas there were over 31,000 total deaths above the recent five-year average – see figure 1. Mortality was running high directly because of COVID but for other reasons as well.

Footnote: Source, ONS. 5-year average based on 2016-2019 & 2021.

The cause of high mortality in 2022 is a topic of debate but, aside from COVID itself, it includes healthcare reasons you will be familiar with from the front-page news: record NHS waiting lists1, ambulance delays2, A&E waiting times related to clinician, bed and social care pressures3 and late diagnosis of diseases4. The number of deaths occurring at home has also been consistently above average over the period, through a combination of ambulance delays and personal choice. These factors are significant but also controllable – I expect them to continue into the next few years but could be overcome in time with sufficient government support and public funding for health and social care.

However, there are several mortality factors of concern that are more challenging to control. For example, COVID has been on the rise again in the UK, with a spike in new infections and hospital admissions before Christmas, supporting the view that it may be here to stay as an endemic disease like annual flu (which itself spiked before Christmas for the first time since the 2019/20 winter). There is also evidence of the waning efficacy of COVID vaccines which puts pressure on maintaining booster programmes. Furthermore, observed deaths from all causes are currently elevated and there is evidence that COVID may increase the likelihood of suffering from severe diseases in future, including diabetes, circulatory disease, chronic kidney and liver damage. Put another way, there is the potential for a permanent worsening in quality of life and longevity for anyone who has contracted COVID-19.

The significant level of mortality in 2022 will only have had limited impact on a pension scheme’s liability value from members recently dying earlier than expected. What matters more is the impact of these factors on the future path of longevity. For example, if endemic COVID created an additional 15,000 deaths from respiratory disease each year, it would reduce life expectancies by 1%. The CMI is expected to allow for 2022 data in the core version of their 2022 mortality projections model, but they are consulting on the model in January 2023 and it is likely that less emphasis will be placed on 2022 data than would have been the case with a business-as-usual update. This will dampen the headline 4% impact of the latest data on life expectancy, which I expect to be something closer to a 2% reduction in life expectancy (and closer to the expectation set by the Pensions Regulator in its April 2022 annual funding statement, although this preceded the latest data).

1. 7.2 million people waiting for elective care in December 2022 – BMA

2. Mean response time in England for category 2 heart attack and stroke calls has been above 40 minutes since Summer compared to the 18-minute target – NHS England

3. Proportion of people waiting more than four hours in A&E in England breached 40% for the first time in April 2022 and was at 46% in November – NHS England

4. There are 1 million missing European cancer diagnoses according to analysis published in the report European Groundshot – Addressing Europe’s Cancer Research Challenges: a Lancet Oncology Commission