Recent years have seen the sports industry become further globalised as high-profile events shift away from their traditional geographic centres of gravity. While this pivot to new and emerging markets presents a host of benefits for those involved in the sector, the expanding footprint of elite sport also means that the influence from – and challenges brought about by – the geopolitical landscape have similarly expanded. The war in Ukraine serves as a stark example of how heightened tensions can rapidly impact sport in several ways, and as the sector pursues new opportunities – in the Middle East for example – we consider the potential threats to the security and reputation of organisations.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the return of interstate conflict in Europe led to extensive repercussions for stakeholders across sport and laid bare the sport sector’s exposure to significant geopolitical developments. Initially, the invasion prompted a series of unprecedented punitive measures against Russian competitors, with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) banning Russian athletes from participating in sporting events just days after the invasion began. FIFA and UEFA, two of the world’s leading football bodies, responded similarly, preventing the Russian national teams and clubs from competing in their competitions. Other international sports bodies followed suit, with the combined reaction of the sporting world signalling a marked change in attitude, underscoring the seriousness with which the invasion was perceived.

Financially, the invasion led to widespread consequences that transcended borders as organisations have moved to decouple themselves from Russian financing, as well as reacting to international sanctions and resulting economic factors. Within a day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, UEFA cancelled its long running sponsorship agreement, worth approximately 40 million euros annually, with Gazprom – a Russian controlled energy entity – and relocated the 2022 Champions League final that was due to be staged in St. Petersburg. At club level, Manchester United Football Club was forced to terminate a lucrative sponsorship deal with the Russian airline Aeroflot while former Chelsea Football Club owner, Roman Abramovic, was forced to sell the club following United Kingdom government sanctions FIFA also took the unprecedented move of opening an emergency transfer window to allow players based in Russia and Ukraine to suspend their contracts and sign for teams in other countries to escape the conflict. This move was in part implemented for the sake of Individual footballers but was also made in the wake of a rapidly devaluating Russian rouble following global sanctions against Russia. Sanctions meant some Russian clubs faced difficulty paying players’ wages, which were often done so in euros. This rule, however, proved costly for some Ukrainian football clubs, who lost tens of millions of euros in player transfer revenues as many foreign players left for other clubs, leading Shakhtar Donetsk to seek 50 million euros in damages from FIFA.

Whilst financial losses have undoubtedly posed serious issues for sporting organisations across the world, in Ukraine the effects of the war have been far more pronounced, as conflict risks have directly threatened its sportspeople and infrastructure. On 2 April 2023, Ukrainian Sports Minister, Vadym Huttsait, stated that the conflict had led to the deaths of at least 262 Ukrainian athletes and the destruction of 363 sports facilities. Following this announcement, Huttsait continued to maintain that Russian athletes should not be able to compete in international sporting competitions.These comments came following a recommendation by the IOC to allow the gradual return of Russian and Belarusian athletes as neutrals, highlighting the difficult balancing act sports bodies must maintain in the face of a constantly shifting geopolitical landscape.

Despite these unparalleled actions in response to the invasion of Ukraine, accusations have been levelled towards many sporting bodies accusing them of having acted out of self-interest rather than a desire to punish and negate Russia’s hostile actions in the international system. Certainly, these charges appear to ring true upon considering the willingness of many in the sporting community to ignore previous acts of perceived Russian aggression toward Ukraine throughout the past decade.

The hosting of major sporting events has long featured as part of the foreign policy toolbox of many states, with there being many examples – both historic and contemporary - of countries seeking to enhance their international standing through sport. In recent years, Middle Eastern states with the financial means to attract globally significant events, including the football World Cup, have been particularly active in this regard, while also making significant investments in their domestic sporting apparatus and in foreign markets.

The hosting of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar provides a useful case study of the challenges associated with holding such events outside of what can be considered their traditional geographic markets. For the World Cup in Qatar – a tiny state without the pre-existing capacity to host such an event - this meant ensuring that all necessary logistical and infrastructure capacities were achieved. This included building or upgrading stadia, transportation systems, accommodation, and other facilities. Furthermore, highlighting practical sporting and scheduling challenges, Qatar’s bid had promised that the stadia would be equipped with cooling systems allowing the pitches, training sites, and fan zones to be kept under 27°C, thereby allowing the tournament to be held in its traditional spot during the summer of the Northern Hemisphere. However, organisers began to back away from these promises, conceding to the fact that the tournament would need to be held in the winter, a massively disruptive and extensively impactful change for stakeholders.

This included European football federations who needed to interrupt their respective leagues’ fixtures, American broadcasters forced to show the event at the height of the American football season, and traditional FIFA World Cup partners and sponsors of cold and/or alcoholic drinks that see a boost in sales during the summer months. Moreover, initial plans for Qatar to construct nine state-of-the-art stadia and refurbish three others were cut by a third, citing financial reasons. The monetary challenges that hit Qatar are indicative of the financial uncertainty facing petroleum-based economies, whose ability to finance such mega projects could be – and in the case of Qatar, were – impacted by the massive drop in price of oil between 2014-2021. While petroleum- based economies like Qatar can boast significant levels of financial capital, such a state of affairs is not guaranteed as a result of fluctuations in markets, and the sport sector must be prepared for how changing economic circumstances can majorly impact upcoming sporting events.

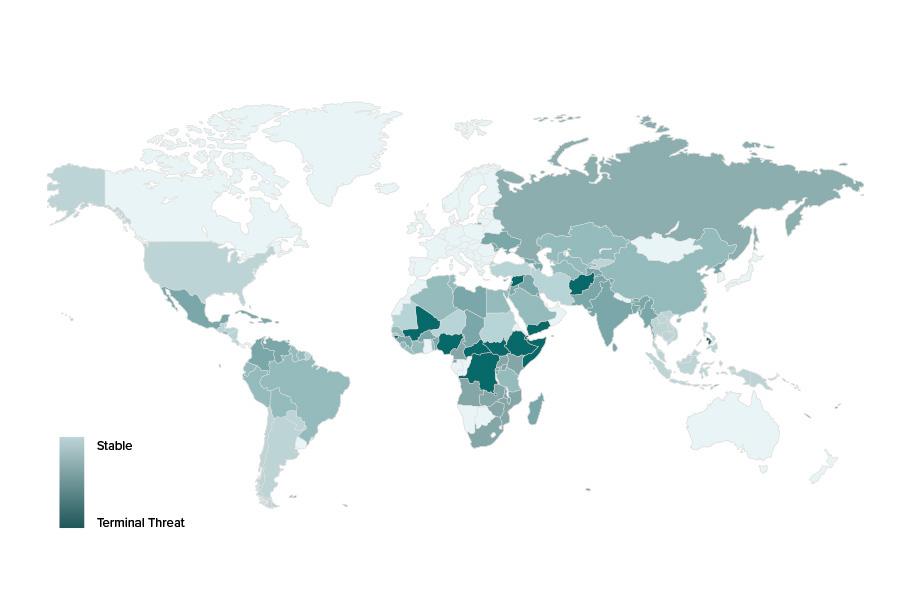

In addition to more practical and sporting considerations, the shift towards new frontiers also risks exposing all stakeholders to security threats present in these regions. Notwithstanding the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war, the security environment of Western European, North American, and Latin American states, have historically proven to be more stable and conducive to the holding of major sporting events, compared to much of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. Conflict, trans-national terrorism, and widespread domestic unrest have all proven to be significant challenges across numerous states.

Source: SCR Risk Intelligence Platform

The decision by some emerging markets – that typically have much higher levels of inequality and poverty compared to their Western peers – to host mega sporting events risks sparking political instability and/ or civil unrest, as they can struggle to justify the costs to their impoverished citizens. Protests, social unrest, and political tensions can jeopardise the safety of athletes, officials, and spectators, leading to the potential cancellation or relocation of the event, as well as putting off sponsors, afraid of having their brand associated with such an event. The 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil saw dozens of demonstrations against the cost of the stadia, corruption, police brutality, and evictions – which often degenerated into violent clashes with security forces – take place across tens of Brazilian cities. Once again, the risk to sporting event stakeholders was pronounced; the British public broadcast television network ITV saw its studio windows in São Paulo cracked by nearby stone-throwing demonstrators. Moreover, at least 17 journalists – including some from CNN, Reuters, and The Associated Press – were reported to have been hurt or attacked during the unrest.

While unrest over the fiscal commitment to major sporting events has drawn the ire of citizens in more impoverished regions, the high-profile nature of sport has led to numerous recent cases of it being targeted by disruptive protests staged by activists over issues including climate change and animal rights. Such trends illustrate that even events held in more relatively secure and stable environments are susceptible, with the increasingly digital lifestyle embraced by citizens in these settings adding a further dimension of online activism that can have implications for the reputational stock.

The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine highlighted how the fabric of international sport can be altered indirectly by events such as interstate conflict. Sport is a high-profile target that has also found itself directly impacted by the actions of violent non-state actors such as insurgents and terrorists, who have long sought to exploit the high-profile nature, extensive media coverage, and large crowds associated with major sporting competitions. Indeed, between 1970 and 2019, there were 74 terrorist plots targeting sporting venues, causing the deaths of 213 people and injuring 699. Just short of 90% of these attacks were bombings or explosions and nearly 50% of attacks were aimed at football venues or stadia. In Pakistan, in 2009 an attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team’s bus by approximately a dozen gunmen, reportedly from the Afghan-based jihadist group Lashkar-e-Jhangvi meant international cricket teams refused to play in the country for ten years. This event also meant Pakistan was stripped of its hosting duties for the 2011 Cricket World Cup by the sport’s governing body – both of which were serious penalties for the nation which hails cricket as its biggest sport.

A further example of sporting events being targeted by terrorist groups was seen in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia’s military intervention in Yemen has resulted in the Kingdom being targeted by numerous cross-border drone and missile attacks by the Yemeni Houthi group, some of which have coincided with high-profile events. In March 2021, missiles were intercepted over Riyadh as the city hosted a round of the Formula E World Championship, while the following year’s Saudi Arabian Formula One Grand Prix in Jeddah was nearly derailed by a missile attack on an oil facility some 16km (10 miles) from the racetrack. Ultimately, despite the nearby attack and concern amongst race participants and spectators, the event went ahead. Although attacks by the Houthis did not inflict direct harm to personnel or assets linked to the sporting events in Saudi Arabia – aside from causing some disruption due to flights being cancelled – it served to highlight their cause using sport as a backdrop.

Looking ahead, the sporting industry will remain exposed to a wide range of risks, broadened further by its ongoing globalisation. As evidenced by ongoing interstate conflict in Europe, the persistent terrorist threat, and increasing awareness of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) issues such as human rights and climate change, stakeholders in sport must find effective means to prepare, mitigate, and effectively handle the growing range of issues they are likely to face. Nevertheless, the issues facing stakeholders will remain varied and dependant on factors such as the geographies in which they operate, the profile of their sponsors, fans, the very sport itself, any links they have with states, industries and organisations, and many other factors. As such, stakeholders operating in the sector must ensure they have insurance in place which is carefully considered and appropriate to the potential level and range of risks they face.

WTW offers insurance-related services through its appropriately licensed and authorised companies in each country in which WTW operates. For further authorisation and regulatory details about our WTW legal entities, operating in your country, please refer to our WTW website. It is a regulatory requirement for us to consider our local licensing requirements.