China, Iran and Saudi Arabia: The coming out moment

On 10 March 2023, Wang Yi, China’s highest ranked diplomat, stepped in front of cameras in Beijing to announce a seemingly remarkable diplomatic achievement: the resumption of relations between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Standing side by side with Wang were Ali Shamkhani, secretary of the Supreme National Security Council of Iran and Musaad bin Muhammad al-Aiban, Saudi Arabia’s National Security Adviser. The Iranian-Saudi enmity over the years has resulted in mutual animosity and the complete severing of all diplomatic relations between the two countries. However, the most significant element of the resumption and normalization of relations between the two regional powers has been at least twofold, both pointing to what appears to be an undeniable reality: China’s growing conspicuousness in acting as a key facilitator in international affairs, a role it has traditionally shunned in favor of a lower profile in its global relations.

First, China’s foray and lack of reticence in brokering a truce represents a new Chinese approach towards the world, one marked by assertiveness and confidence. While China has long abided by Deng Xiaoping’s doctrine of “hide and bide,” China no longer feels the need to be deferential in conducting its foreign relations. Beginning with China’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy[1] during the COVID pandemic, China under President Xi Jinping appears much more willing to delve into affairs that it views as crucial to its larger strategic goals. Given the relative importance of the rapprochement between the two rivals, it is highly likely Xi had a direct role in the negotiations, having visited Riyadh in December[2] and hosting Iran’s president in Beijing just last month[3]. China may view this deal as serving as the foundation of a new geopolitical reality in not only the Middle East but beyond as well, most notably in other conflict areas such as Myanmar and Yemen. After China’s brokering of the deal, Xi called on China to “actively participate in the reform and construction of the global governance system” which would add “positive energy to world peace and development.”[4]

Secondly, China is positioning itself as a responsible mediator to much of the non-Western world intent on what it calls “win-win” collaborations and deepening economic ties via trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). In sharp contrast to the United States’ unilateral pullout from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or the Iran nuclear deal) during President Donald Trump’s tenure, both Iran and Saudi Arabia calculated that Beijing would serve as the surest guarantee of any agreement reached. Due to China’s longstanding political and economic ties to both countries – and coupled with Xi’s personal buy-in – Iran and Saudi Arabia deemed China as a critical and trusted broker between the two. China saw the United States’ animus towards Iran and lack of official diplomatic relations with Tehran, as well as America’s fraying partnership with Saudi Arabia, as a comparative advantage, one which China could deftly exploit to its benefit. What has resulted is a sidelining of the United States, who has long been the primary actor in the Middle East for nearly eighty years – and with this agreement, China has positioned itself virtually overnight as an alternative – and potentially, as a long-term replacement – to the United States.

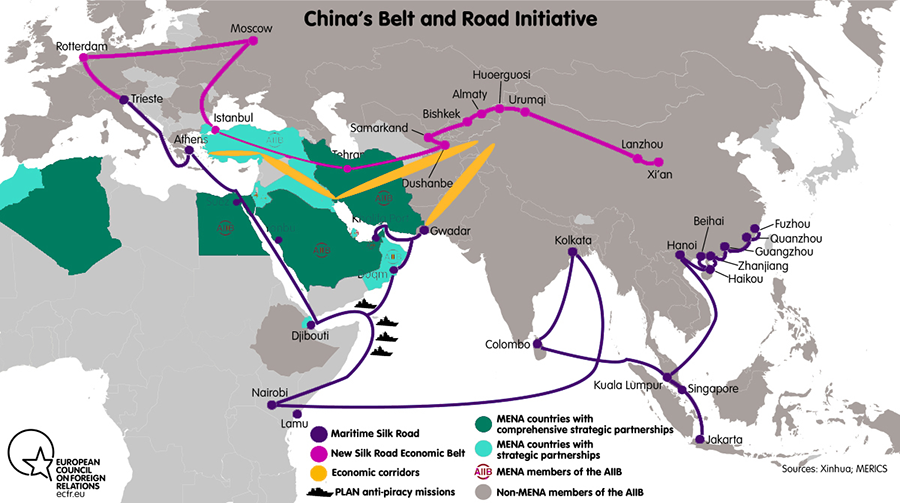

Though the agreement should be judged in a realistic manner, the successful negotiation of a détente between Saudi Arabia and Iran represents a milestone achievement for China. China’s place as both countries’ number one trade partner should be of no surprise; however, what looms larger for China is its large, infrastructure-driven development projects linking the entirety of the Eurasian landmass as well as Africa and Latin America through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Maritime Silk Road. Currently, China’s security engagements are not concomitant with its economic interests. Protecting Chinese-run and designed railways, ports, roads, industrial parks, and the Chinese diaspora throughout the world would require a commitment that Beijing is simply unable or unwilling to meet currently. Given its precarious position as a large importer of key natural resources, China has a vested interest in Middle Eastern stability and continuity in resource-heavy regions such as Iran’s Khuzestan Basin[5], Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province[6], and key transit corridors such as the Persian Gulf and Red Sea.

Building upon the initial diplomatic success of the Iran-Saudi agreement, China is now aiming to interject itself into the Russia-Ukraine war as a possible peacemaker. However, China’s position has been heavily criticized by both the United States and Europe due to Beijing’s close proximity to Russia. Immediately preceding the Russia-Ukraine conflict in early 2022, the two countries released a 4,000-word document entitled the “Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development”[7] during the opening ceremonies of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. Broken down into 4 parts, the declaration proclaimed a “no limits” friendship between the two countries, touching upon issues as diverse as multilateral institutions, the international order, Arctic development, the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, and larger economic relations between the two countries. This declaration was widely regarded as a sui generis agreement that added a new element to Russo-Chinese relations, and which the European Parliamentary Research Service regarded as a potential “quantum leap”[8]. Demonstrating the two countries’ closeness, Xi Jinping attended a three-day state visit to Russia in March, making a pointed comment to President Vladimir Putin that the world is currently experiencing changes unseen in a century, and that China and Russia are the key actors driving this change[9]. On the Kremlin’s website, President Vladimir Putin hailed the strategic partnership between the two countries as contributing to a “more just and democratic multipolar world order[10]”. Both China and Russia pledged to further deepen their security cooperation and economic links, with the summit taking place just days after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for the Russian president[11].

Both China and Russia pledged to further deepen their security cooperation and economic links…

The joint press statement also made reference to the Ukraine crisis, with Russian officials expressing positivity towards China’s peace plan. Put forward by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs on February 24th, the 12-point plan enumerates several provisions which include conditions such as respecting the sovereignty of all countries, ceasing hostilities, resuming peace talks, and promoting post-conflict reconstruction[12]. Many Western capitals have rejected China’s stance as biased in favor of Russia – however, the White House privately concedes that many nations, especially in the developing world, may show positive receptivity to China’s role as peacemaker[13]. This highlights what the European Council on Foreign Relations calls a “United West, divided from the rest”[14], research further supported by the University of Cambridge’s Bennett Institute for Public Policy that found public attitudes toward international politics are hardening into two opposing blocs, one represented by liberal democracies favoring the United States and a second bloc composed of illiberal, non-Western nations such as China and Russia.[15]

While Europe and the United States have immediately dismissed China’s 12-point plan, China is tapping into prevailing sentiments that permeate the views of the developing world across not only the BRICS nations but many ASEAN, MERCOSUR, and African Union countries. In March 2022, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution condemning the invasion and requesting Russian forces to “immediately, completely and unconditionally” leave Ukrainian territory, with 141 countries in favor, five against, and 35 abstaining[16]. One year later, 141 countries voted for the resolution, seven against (Mali and Eritrea joined Russia this time), and 32 abstentions[17]. Given these dynamics, many European leaders believe China may be the only party capable of convincing Russia and Ukraine to reach a political settlement to end hostilities. With a recent spat of European leaders being feted by Xi Jinping in Beijing such as Germany’s Olaf Scholz, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, and Emmanuel Macron, China is trying to position itself as the “indispensable broker” – with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signaling his willingness to speak with Xi and expressing openness to China’s peace plan[18].

Given these dynamics, many European leaders believe China may be the only party capable of convincing Russia and Ukraine to reach a political settlement to end hostilities.

Ukraine not relinquishing the eastern portions of the country and Russia holding onto the east of Ukraine – it is a tall order for China

However, what are the prospects that a Chinese-mediated agreement between Ukraine and Russia will be successful? As both Zelenskyy and Putin are not willing to provide concessions that either see as detrimentally anathema to their respective country’s interests – Ukraine not relinquishing the eastern portions of the country and Russia holding onto the east of Ukraine – it is a tall order for China to achieve some sort of concrete peace deal. What would a Chinese effort look like? First, due to Chinese sensitivities around the issue of Taiwan, China does not officially recognize the Russian annexation of Crimea or the recently annexed territories of Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson. Point 1 of Beijing’s 12-point peace plan calls for upholding the “sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all countries” which Vladimir Putin said “correlates to the point of view of the Russian Federation.”[19] But both Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian population, nearly 90% of whom, reject offering any sort of territorial concessions.[20] China will have to take into account the political will and concerns of Ukrainian citizens vis-à-vis the legal framework of Ukraine as previous efforts at negotiations around contentious issues such as NATO and EU accession, the 2014 Minsk agreements, or autonomy for the eastern regions proved futile and tenuous.

Second, for peace efforts to make way, both Ukraine and Russia will have to be incentivized that making peace is more in their interests than continuing the conflict. Ukraine has sought to appeal to developing nations such as Egypt, Malaysia, and India given Ukraine’s position as an important breadbasket and key exporter of crucial commodities. India’s current role assuming the G20 Presidency will offer a forum for Ukraine to raise its concerns and offer up its plan to end the war. Despite India being a crucial arms importer of Russian weaponry, such an entreaty by Ukraine can provide an opening for developing states to contribute their peace proposals on ending the conflict. In this regard, and to brandish its multilateral diplomacy, China may enlist the assistance of the likes of countries representative of the viewpoints of developing nations such as South Africa, Turkey, Brazil, Indonesia, and India to create a Global South framework that would serve as the basis for a negotiated settlement. But as many European and American officials consider China a direct party to the conflict, such a likelihood is highly improbable. Echoing this viewpoint, Dr. Orville Schell, head of US-China relations at the Asia Society and a WTW consultant, believes China’s aspiration to serve peacemaker in Ukraine will be tainted due to Beijing’s rhetorical support for Russia: “This is an extremely challenging aspiration without Beijing first making some more fulsome condemnation of Russia’s violation of the Ukraine’s sovereignty. For the Chinese Communist Party, the sanctity of sovereignty has – theoretically, at least – been a non-negotiable principle. However, they have clearly abridged this principle in this case. Unfortunately, China’s shared sense of grievance with President Putin finally makes it unlikely that Xi Jinping will criticize Russia in a way that would allow him to play a meaningful role as a neutral force to bring the two sides together.”

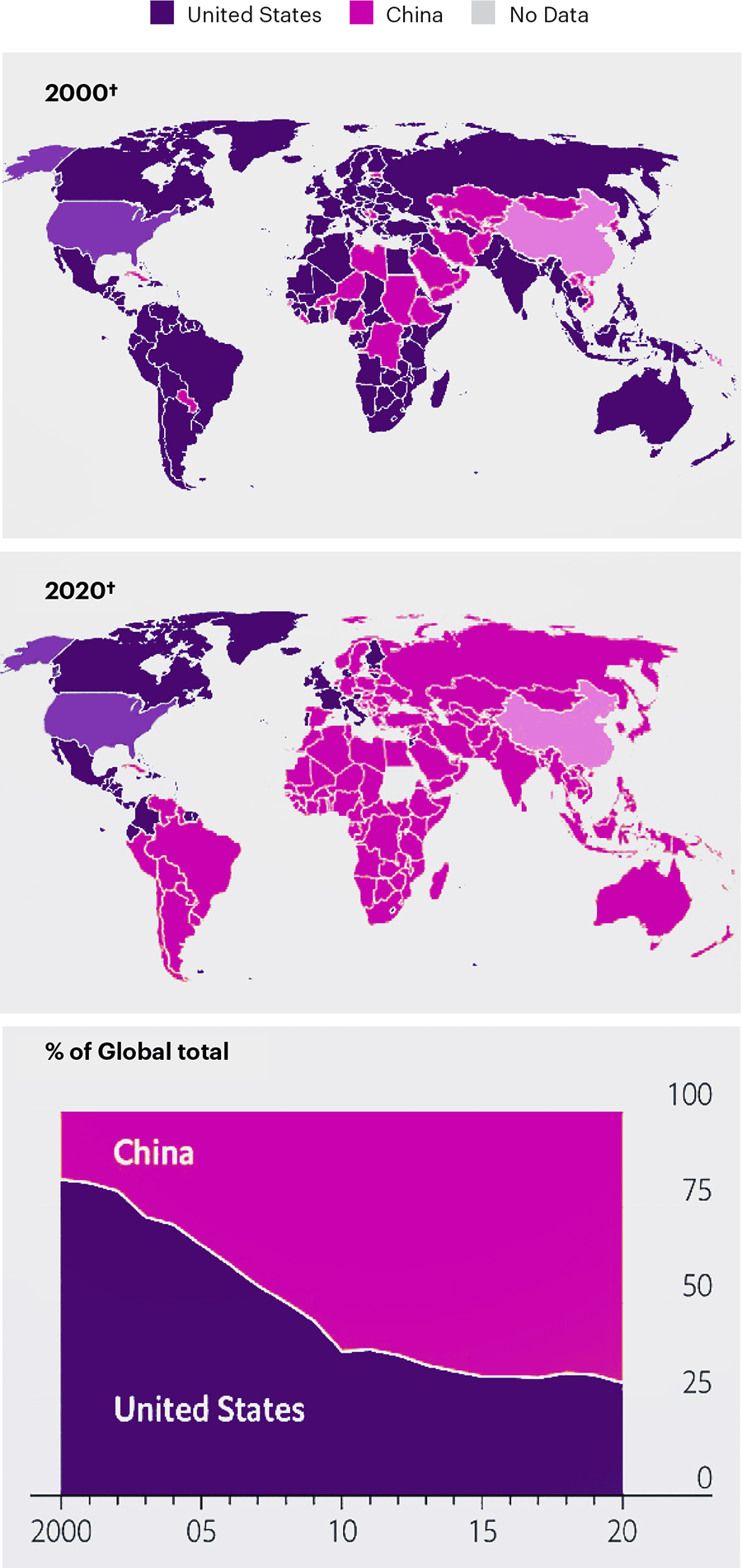

Should China’s efforts in the Middle East and Ukraine/Russia be seen as unique and a one-off attempt towards conflict mediation or will this be a new trend of Chinese foreign policy? Were these efforts as surprising as some have termed them? In much of Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America, China’s economic growth in recent decades has had a multitiered effect of promoting Chinese cultural and soft power, increasing China’s diplomatic presence, bolstering the brand of “China, Inc.”, and serving as an alternative model that has predominated amongst wealthier, more industrialized countries of the North Atlantic and East Asia. China has seen its trade status with much of the world increase manifold as a result of the country’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, supplanting the US as the world’s principal trading partner. Naturally, Beijing believes that its diplomatic heft should follow its economic rise – and an international order reflective of these new power dynamics.

Source: The Economist

Source: Centre for the Future of Democracy University of Cambridge.

Outside of its immediate area of the Asia-Pacific region, China’s stratagem of diplomacy and developmentalism can be looked at in stark contrast to the United States’ heavily securitized approach as evidenced by the latter’s anti-terrorism efforts in the Sahel, counter-narcotics operations in Latin America, deepening military alliances amongst the Central and Eastern European countries in NATO in the wake of the Ukraine conflict, and creating new military agreements in its Asian hub-and-spoke alliance system such as the AUKUS agreement. China has embarked upon a vastly different approach, one less reliant on military alliances and instead centered more on commercialism, investments, and a heavy diplomatic presence. China is currently now the second largest contributor to the United Nations’ regular budget[21], the second biggest financial contributor to the UN peacekeeping budget behind the United States[22], and has the most prolific diplomatic footprint of any country in the world. In 2009, as part of the country’s “going out” strategy, Beijing expressed its intention to utilize the country’s large foreign exchange reserves to support expansions by Chinese companies in both developed and developing economies[23]. Elisabeth Braw, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and a WTW consultant, describes China’s approach as “attempting to form a new bloc based on trade, and to achieve this ambition it's working hard to line up allies. These countries don't need to be China's best friends; they just need to be countries willing to engage in significant trading with China without criticizing its human rights record or any of its other politics. As China's intensifying contacts with Iran and Saudi Arabia illustrate, there are plenty of such countries.”

Source: FT

India’s current role assuming the G20 Presidency will offer a forum for Ukraine to raise its concerns and offer up its plan to end the war.

China’s policy path of commercial symbiosis and dependency is exemplified by recent trade deals such as the RCEP and Beijing’s intention to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership), its place as Taiwan’s largest trading partner, and its position as the top trading partner to more than 120 countries. Chinese trade, loans, investments, and commercial partnerships with much of the world has had net positive effects for globalization, poverty alleviation, and inequality. As China’s economic clout grows, so too has its diplomatic footprint. Currently, China’s foreign policy can now be described as mirroring the dictates of Xi Jinping, whose increasingly personalistic style of governance believes Beijing must play a larger role in global affairs commensurate with China’s international influence. As demonstrated by the recent brokering of the Iranian and Saudi détente, Beijing’s multilateral diplomacy will seek to cultivate certain actors and regions that are critical to China’s core interests.

The cost-benefit analysis of weighing the effectiveness of different alternatives has been represented best by China’s approach to the Ukraine conflict. As the Ukraine conflict demonstrates, not all Chinese mediation endeavors will prove successful as Ukraine was seen as a key target investment country on Beijing’s ambitious BRI project, with Kiev signing a joint action plan with China and officially joining the project in 2017.[24] Given in recent days a flurry of international leaders being courted by Beijing, Beijing’s definitionally-ambiguous diplomatic proposals – the Global Security, Development, and Civilizational initiatives – demonstrates a new willingness and capacity to take on new roles. Such initiatives should not be dismissed out of hand as Chinese conceptions of commercialism and civilization have great resonance in the developing countries of the Global South. Going forward, China will continue to develop itself into what it regards as a “comprehensive national power” – which will automatically necessitate undertaking new approaches that it has heretofore shied away from.

Chinese trade, loans, investments, and commercial partnerships with much of the world has had net positive effects for globalization, poverty alleviation, and inequality.